At CARE, we’re taking two approaches to learn more from failures in our work. First, we’re using a podcast series where people talk about what’s gone wrong in their work, and what they think other people can learn from it. That case-study approach is helpful providing a human face and details around specific problems that others might be facing. It also builds on the networks in the organization, where people who listen can follow up with an individual to learn more. The podcast model taps into the way we usually talk about what goes wrong: informal storytelling between colleagues.

But “the plural of anecdote is not data.” So we’re complementing the podcasts with a meta-analysis of our project evaluations from the last few years to see what’s going wrong at an organization-wide level. The meta-analysis looks at “failure” trends across more than a hundred projects where the evaluator cited areas that we could improve or obstacles that may have slowed or reduced project impact, to identify opportunities for action an organizational level. This pulls away from the idea of failure as being individual and specific—and maybe something that only happens in “bad” projects—and looks at failure as symptoms of bigger issues we can address more comprehensively.

Here’s an example: In CARE’s Gender Equality Framework, we highlight three domains of change: agency (a woman’s individual skills), structure (the laws and structures that shape her environment), and relations (her family, friends, etc. and their expectations of her). While agency rarely appeared as a challenge, 23% of evaluations pointed to structural barriers women faced that projects hadn’t addressed. So, we’ve got training for individual women worked out, but need more support on how to help projects tackle bigger structural issues for women. Our Gender Justice team is building its workplan to include more tools and resources for project teams on this issue—and they now have more data confirming that all three elements of the framework matter to programs.

Building from our global failure data, CARE is working with different teams around the organization to figure out how we can strengthen our systems. For example, one key finding is that failure starts early. 30% of projects that had failures highlighted a need for more context analysis. So this year we are re-vamping our design processes to make sure we’re catching issues early and understanding the broader contexts our projects operate in. We’re also reinforcing some of our underlying internal systems—like technology and monitoring and evaluation—to make sure that individual teams have the support they need to avoid other common failures.

This is still a work in progress, but we already have some lessons that we think might help others learn more from failure—including our own.

A ‘pre’mortem’ exercise on the podcast project, in which project teams brainstorm possible areas of failure and responses, before a project starts

- Openness starts at the top: For the podcasts, we started with top leaders talking about critical organizational misses and ways to improve. Some project managers also took advantage of the podcast opportunity to launch new ways to talk about failure with their project teams. This helps other staff see that learning from what isn’t working is supported and even expected, across the organization.

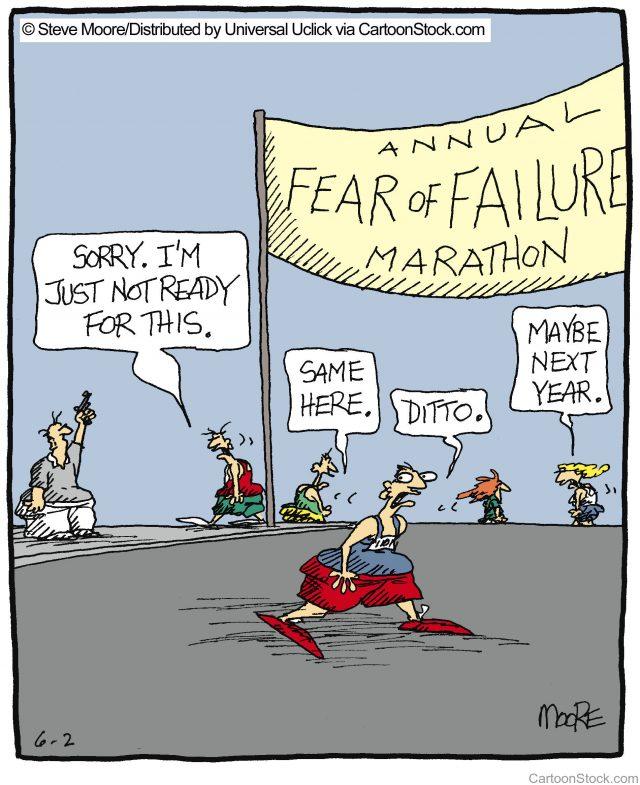

- Focus on action: Being willing to talk about failure isn’t enough. We have to be ready to change our work so that we’re making smarter mistakes in future (zero failures isn’t the goal, since we’ll always be trying new ideas, and they won’t always work). Both the podcasts and the trends analysis are focusing on action plans, and how we can improve our activities and systems.

- Pair stories with data: it’s been very powerful to have broader data trends coupled with specific case studies. It lets us make a case that few failures are purely the fault of project staff, and devise action plans for organizational support. At the same time, the case studies provide the richer detail and practitioner insight we need .

- Networks matter: We’re building on existing networks and communities of practice to both share the data and create action plans. For example, our monitoring and evaluation community of practice not only looked at the detailed information about what goes wrong with Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability & Learning (MEAL), they also came up with some solutions we can enact right away. Our UK office requires management to create an action plan to address weaknesses identified in evaluations (and to follow up to ensure those plans are implemented), so the CARE UK MEAL team is helping other global teams replicate that model.

We’re still trying to figure out some of the answers. This approach has a lot of advantages, but we need to get faster at identifying failure trends. Because we’re looking at final evaluations, many of the failures in our meta-analysis started 3-5 years ago. If we want to address failure more effectively, we need to spot it faster. The Harvard Kennedy School’s Building State Capability program recommends checking in on activities every two to three weeks because mistakes aren’t failures yet after only a few weeks. We’re still looking for more effective ways to do that at an organization-wide level.

We’d also love to hear from others who are working on this. While some of the challenges we’ve seen are no doubt specific to CARE, many reflect broader challenges in the international development space. Having some structured reflection on systemic challenges—across donors, geographies, and sectors—is one way we can all work together to improve impact in programming.

About the Author

Emily Janoch is Senior Technical Advisor on Knowledge Management for the CARE USA Food and Nutrition Security team focusing on ways to better learn from and share practical experience on eradicating poverty through empowering women and girls. She focuses on learning from programming and using that learning to improve impact.

With four years of on-the-ground experience in West Africa, 10 years of development experience, and academic publications on community engagement and the human element in food security in Africa, Emily is especially interested in community-led development. She has experience in food security, nutrition, health, governance, and gender programming, and has a BA in International Studies from the University of Chicago, and a Masters' in Public Policy in International and Global Affairs from the Harvard Kennedy School.

This blog first appeared on the Oxfam Blog and was published here with permission.

Add the first post in this thread.