Is it possible for conservationists to believe in the myth of “the wild” anymore?

Who but conservationists can better understand the ways in which the natural world has diminished by human impact? Our species has forced its presence into the lives and environments of wildlife around the globe, to the farthest reaches of this mythical “wild” that we still envision as existing somewhere beyond our society’s borders. But plastic pollution turns up in previously untouched corners of Antarctica, migrations pass through cityscapes filled with lights that throw birds off course and into the windows of skyscrapers, large carnivores that should be the unimpeded champions roam the outskirts of cities and freeways, and vast open oceans shrink to the spaces between shipping lanes full of noise and regions full of indiscriminately deadly fishing gear.

Photo of Thunderbird by Miquel Gomila

Conservation technology offers to us a fuller understanding of our impacts. We can map the shrinking forests lost to land development or climate-driven disasters. We can track the ranges of wildlife and see where they intersect with our own. We can survey populations to observe their declines.

"By allowing technology to show us stories of conservation failures, can we begin to see a clearer picture of what we have already done to nature, and what needs to be done?"

On a more optimistic note, conservation technology offers to us the promise of future solutions to these same problems. If we do not understand our impacts, we cannot fix them. Likewise, if we do not accept the failures and limitations of our knowledge and current solutions, we cannot hope to improve the world that we have so drastically changed. By only acknowledging the successes of conservation technology and positive stories of progress in conservation, do we buy into that myth of “the wild,” banking on the idea that we can still preserve nature as some standalone world independent of our own? And by allowing technology to show us stories of conservation failures, can we begin to see a clearer picture of what we have already done to nature, and what needs to be done?

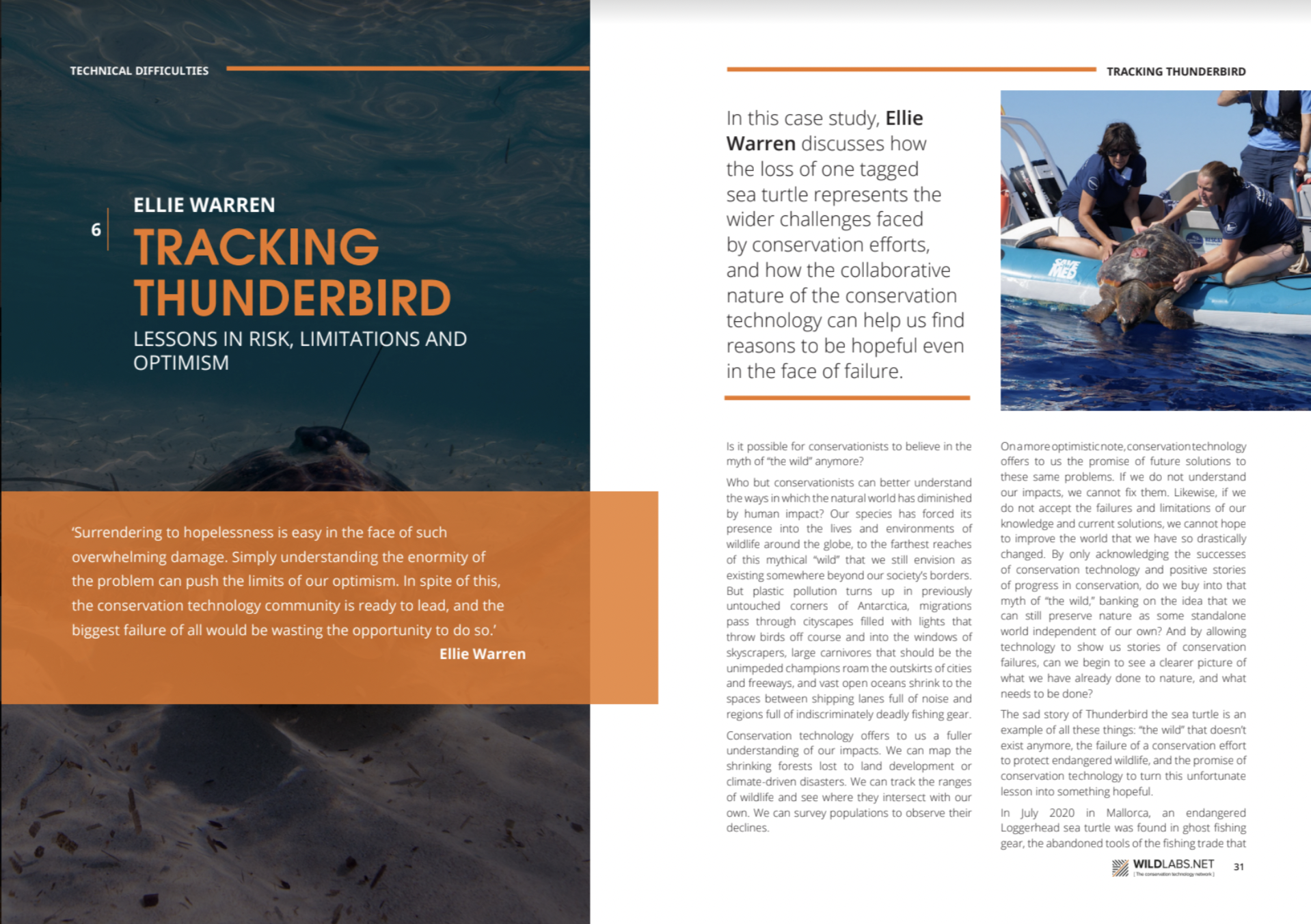

The sad story of Thunderbird the sea turtle is an example of all these things: “the wild” that doesn’t exist anymore, the failure of a conservation effort to protect endangered wildlife, and the promise of conservation technology to turn this unfortunate lesson into something hopeful.

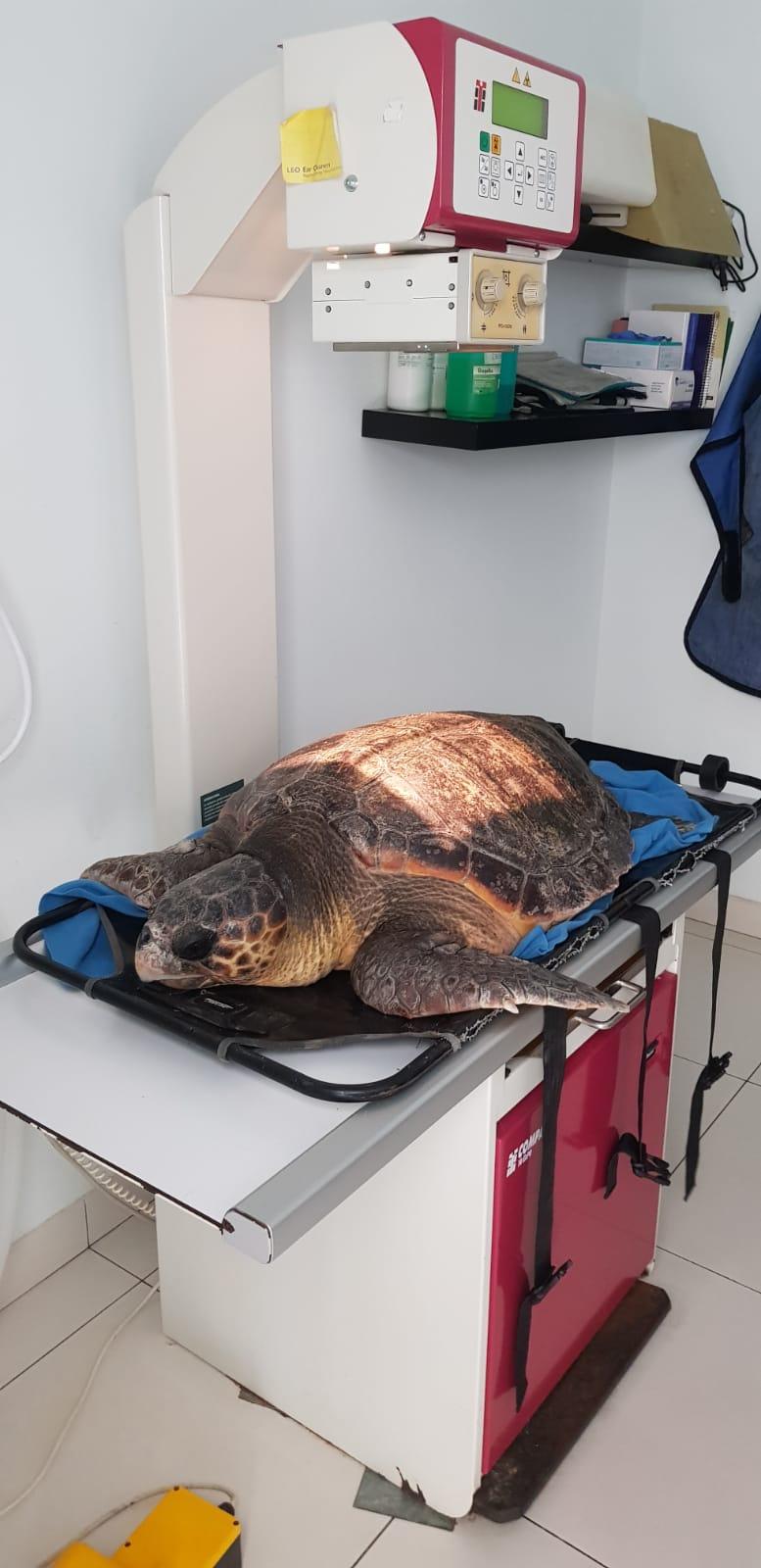

In July 2020 in Mallorca, an endangered Loggerhead sea turtle was found in ghost fishing gear, the abandoned tools of the fishing trade that entangle countless other marine megafauna every year. An appropriate name, considering ghost gear allows human impact to linger, haunting wildlife long after we’ve left that area behind. Thunderbird was lucky enough to be rescued by the Save the Med Foundation from what is too often a fatal trap for other endangered sea turtles. At the Palma Aquarium rescue centre, Thunderbird received care and recuperated from her run-in with ghost gear, making a full recovery. Dr. David March of the universities of Exeter and Barcelona attached a satellite tag to Thunderbird’s shell in preparation for her re-release back into the sea.

Photo by Palma Aquarium Foundation

As one of several turtles tagged for the “Oceanographic Turtles" programme, jointly conducted by the Balearic Islands Coastal Observing and Forecasting System (SOCIB), Alnitak, Palma Aquarium Foundation, and the University of Exeter, and with the support of NOAA NMFS, Thunderbird would provide insights into migration paths and turtle behaviour. The satellite tag returned data on location, depth, and water temperature, and researchers used the critical data from tagged turtles to collaborate with fishermen on developing the risk management measures needed to prevent things like bycatch fatalities and collisions.

WhenThunderbird was returned to the ocean with her new satellite tag, this seemed to be a conservation success story. Though this turtle had nearly been killed by human impacts, humans had also saved her, and would now provide data to help us understand and protect her species. By all accounts, the tale of Thunderbird should’ve had a happy ending. It doesn’t. But that doesn’t mean the story is any less worthwhile.

Thunderbird was not returned to “the wild” as we’d like to believe - she was returned to an ocean that, despite her lucky survival the first time around, was still just as full of danger caused by humans. To make her way out of the Mediterranean and through Gibraltar Strait, Thunderbird had to navigate the Alboran Sea, a path that led her directly through an area with strong currents and marine traffic. Because of the risk that she’d be caught or injured again by a collision, the local network of the Mediterranean Ghost FADs were asked to be on alert, with Thunderbird's tracking data providing invaluable information that could allow intervention in the case of another incident.

Photo by Save the Med Foundation

Thunderbird successfully made it into open waters, and the team anticipated that she would swim toward America, as many loggerhead turtles living in the Mediterranean are born in Florida or the Caribbean. To their surprise, Thunderbird instead took a path along the West African coast, likely because she was one of a small number of Western Mediterranean turtles born in Cape Verde. This data, then, could also be invaluable for understanding migrations along this path.

Photo by Save the Med Foundation

Because of the satellite tag, the research team could see that Thunderbird was frequently diving near the sea bottom along the West African Coast. But in February 2021, the satellite tag stopped returning data, its last two locations shown as near Senegal, and finally, in Dakar - on land near the main harbor.

It seemed possible that the tag was malfunctioning; after all, technological failures of biologging gear aren’t uncommon. Another type of technology was called into action to cross-reference the turtle’s last known locations - the Global Fishing Watch portal. By comparing their fishing vessel data to Thunderbird’s recent satellite tag data, the team found that her last recorded dive was in the path of known trawling vessels. These vessels use gear that drag along the seafloor, often causing damage to marine environments and catching species like sea turtles unintentionally. The results of this bycatch are often fatal.

While it’s possible that Thunderbird could’ve been found with a damaged satellite tag and re-released alive, it’s also very possible that she died as bycatch. And while we all hope that Thunderbird somehow survived, her survival alone would not necessarily make this story less devastating. After being saved from human impacts once, outfitted with conservation technology to track her path, and successfully navigating yet another dangerous area full of vessels and risks with humans standing at the ready to intervene if necessary, the fact that Thunderbird still suffered from yet another bycatch event demonstrates just how severe our impacts have been on “the wild.”

After being rescued once, no wildlife should face double jeopardy, finding themselves up against the exact same threat mere months later. But that is exactly what happened, and it happens to countless other animals who, unlike Thunderbird, aren’t monitored, and can’t tell us their story through data. Thunderbird’s story shows that, even with the help of human intervention and technology, the risk to wildlife caused by human impacts is constant, unavoidable, and sometimes inevitably fatal.

While the loss of a tagged animal along its migration path, so close to making it home, may seem like a failure, that is not why I’ve chosen to write about Thunderbird in this series. From a research perspective, the data returned by Thunderbird’s satellite tag was not a failure at all. Her journey - and its unfortunate end - did, in fact, lead to a better understanding of turtle migrations, showing just how present danger is to these endangered species. That data will be much more useful to conservation in the long-run than simply understanding turtle behavior during their migrations; truthfully, there will be no more turtle migrations at all if we do not understand and address that danger in the first place. And because researchers like Dr. March aim to use turtle tracking data to work with fishermen on collaborative solutions, Thunderbird's experiences certainly demonstrate where risk mitigation strategies and response tactics can be improved to prevent incidents like this.

There is no failure in this project from a technological perspective, either. The satellite tag did exactly what it was designed to do - report back Thunderbird’s location, right until the end of her journey.

But this story represents a much more ominous failure, and a much more difficult one to address. The failure is in our own expectations. We expect a rescued turtle to become a sign that our conservation efforts are working. We expect human intervention to offset the rest of the damage caused by humans. We expect that understanding data from conservation technology will translate to impact, hoping that the rest of the world will care about the stories told by that data. And we expect that there is still a natural world for us to protect - a world that is safe for wildlife if they can only make it there, and if we can only help them along the way. If all of the collaborations at work here to rescue, track, and recover Thunderbird were still unsuccessful, even with the help of technology, then what else possibly could have made a difference?

Surrendering to hopelessness is easy in the face of such overwhelming damage. Simply understanding the enormity of the problem can push the limits of our optimism. In spite of this, the conservation technology community is ready to lead, and the biggest failure of all would be wasting the opportunity to do so.

"The conservation technology community is ready to lead, and the biggest failure of all would be wasting the opportunity to do so."

We cannot solve these problems overnight, and there is no magic technological solution that can reverse the damage already done by humans. But there is hope in every story of conservation failure, if you know where to look. In Thunderbird’s story, I see hope in the fact that data from her satellite tag and data from Global Fishing Watch were able to provide a clearer picture of her fate. That technology allows us to understand our impacts, however negative, is at least a starting point. And as technology becomes more and more interconnected, I see hope for better solutions in the future - tools and systems that could allow us to intervene more efficiently, and detect and avoid bycatch in the first place while better protecting environments where endangered species live and migrate.

Dr. David March and his partners are already working to reduce bycatch, adapt fishing gear and methods, and monitor unregulated and illegal fishing in a project funded by the MAVA Foundation and run by the University of Barcelona and Birdlife Internationa. Working with a coalition of partners based in West Africa and internationally, this project will also help to identify bycatch hotspots that pose major threats to wildlife like Thunderbird. This kind of collaborative effort can amplify conservation technology’s impact. On a wider level, it serves as an example of how accepting the failures and realities of our own impact can pave the way to progress.

Photo by Palma Aquarium Foundation

If we cannot preserve a natural world that has already been destroyed, we can perhaps use technology to recreate it to the best of our ability for wildlife. It is still possible to shape our own human world around the habitats and ranges of wildlife, if we choose to do so. The ocean will never be free of fishing vessels and pollution, and “the wild” will never be free of human impacts again. But if technology could, for example, inform where and when we fish, directed by factors like migration paths and the likelihood of bycatch, would that not be a better world for wildlife?

And would it not be a better world for us, knowing that the wild still exists in some form, somewhere out there, because we chose to make it so?

-------------

Thank you to Dr. David March for permission to share Thunderbird's story. To view the data from Thunderbird's migration journey, as well as from the other turtles currently tracked in this project, visit the project map here.

Download the Case Study

This case study is the sixth in our Technical Difficulties Editorial Series. The full series will be available as a downloadable issue in December, 2021. The Tracking Thunderbird case study is now available for download here.

About the Author

Ellie Warren creates content and supports the conservation technology community at WILDLABS through virtual events, fellowships, and community engagement. She currently works as WILDLABS Coordinator at World Wildlife Fund, and has a background in English, nonfiction writing, and screenwriting.

Add the first post in this thread.