The theme of the 2021 Women in Science Day is ‘Women Scientists at the forefront of the fight against COVID-19. Our majority-women WildTrack Core Group is made up of independent scientists working to protect wildlife around the world and prevent human:wildlife conflict. As such, our work is of fundamental importance in reducing the risk of future pandemics.

Our group has a unique focus: we have pioneered the use of cutting-edge technologies for non-invasive wildlife monitoring alongside local traditional ecological knowledge, to ensure a safer future for some of the most threatened species on the planet, and for humans.

Our WildTrack women, pictured below, are delighted to take part in #WomenInScience, recognizing the critical role and unique perspectives the female gender brings to science and technology.

I’m Zoë Jewell, a co-founder of WildTrack, a non-profit focusing on non-invasive, cost-effective and community-friendly ways to monitoring endangered species. The majority-women WildTrack Core Group is unique in being committed to this ethos. We work with a wide range of species in different countries and ecosystems, and we share a passion to deliver the animal-and-human-friendly conservation message around the world. I work primarily helping WildTrack’s 30 field project partners develop and apply new non-invasive monitoring technologies across five continents. Our projects focus on cheetahs in southern Africa, pumas in the Americas, tapirs in South America, Amur tigers and giant pandas in Asia, and otters and dormice in Europe, to name a few. Our footprint identification technique (FIT) has won several awards for identifying the species, individual, sex and age-class of the animal that made them. These data can be used to calculate species numbers and distribution, imperative for any successful conservation strategy. They’re also used to mitigate human/wildlife conflict and used in anti-poaching work. Today we’re scaling up our work to increase our ability to collect and analyse data using smartphone apps, drones, and AI – meshing the ancient art of tracking with cutting-edge technology.

My name’s Margit Bertalan, and early in my graduate studies I partnered with WildTrack to test the capability of FIT in identifying individual eastern mountain bongo in Kenya. I’m currently working as a social science consultant for conservation projects in East and Central Africa. While completing my Ph.D. in Ecology, I focussed on decolonizing conservation and advocating for genuine community engagement and consent regarding conservation initiatives. As the world wakes up to social justice issues in all sectors of society, it’s clear that the conservation field is not free of inequities – there’s a demand for environmental justice. WildTrack uses Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and works to involve local and indigenous communities, as well as the broader public, to make long lasting and sustainable advances in species monitoring and conservation.

I’m Samara El-Haddad, a British/Lebanese zoologist based in Lebanon. For the last two years I’ve been working with local NGOs to conserve wildlife and their habitats. I’m Wildlife Conservation Specialist at Lebanon Reforestation Initiative (LRI), and I’m tasked with finding new, cost-effective tools to study and monitor local wildlife.

Lebanon has and still is facing major threats to its biodiversity. Several conservation and restoration initiatives are taking place, however their focus is on conservation and restoration of flora, leaving an obvious gap in research relating to fauna conservation and its integration into broader ecological restoration. In Lebanon we lack basic data information about species populations, densities and their geographical distribution. So my work at LRI involves developing research on fauna which will help improve our national conservation practices, guidelines, and policies.

We’re now partnering with WildTrack to use their footprint technology locally to gather information about Eurasian otters and to create a reference dataset of footprints of our other mammal species. If we can successfully use this non-invasive tool to monitor otter populations locally, we’ll expand our work to other endangered species in Lebanon.

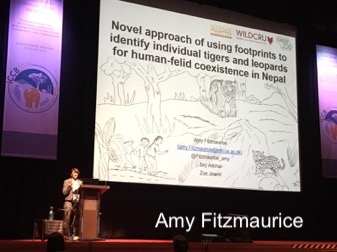

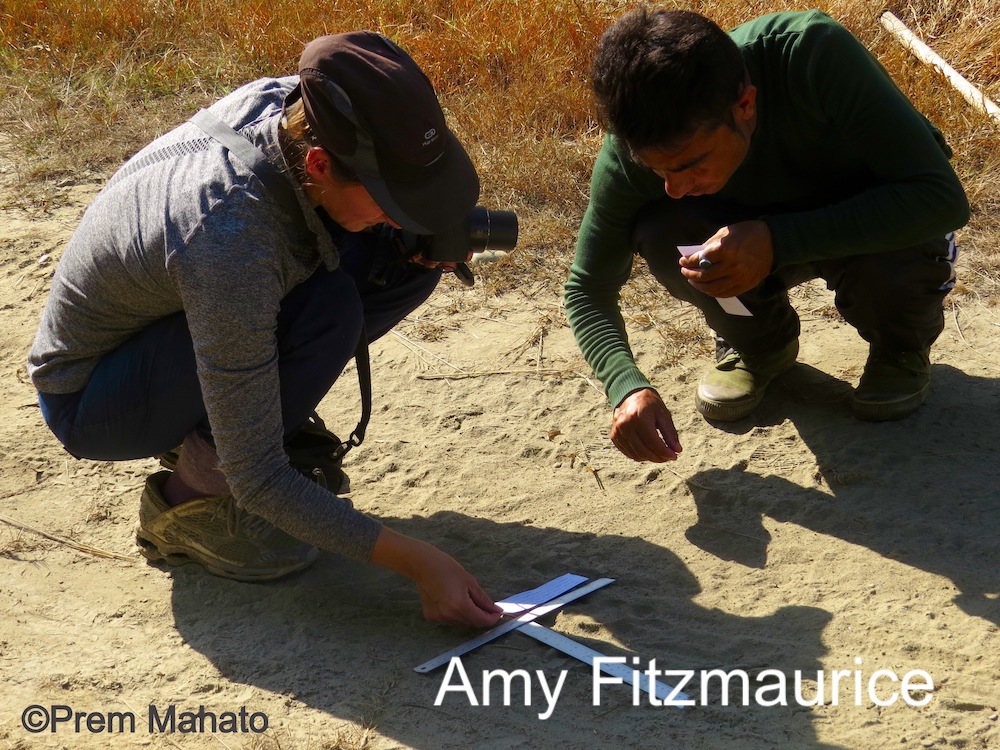

Hello, I’m Amy Fitzmaurice, a conservation scientist undertaking cross-disciplinary work on social science and conservation biology. Based at WildCRU, University of Oxford, I’m an advocate for community-based conservation work, ethically-minded research and conservation, and, of course, non-invasive monitoring techniques. It’s important that these are made widely accessible to ensure as many people as possible can contribute towards conserving endangered species. I’ve been part of WildTrack since 2016 and use FIT to study tigers and leopards in Nepal. We’re in the process of creating a database of their footprints to identify as many individuals as possible. We can use this as a cost-effective and fast method to identify animals involved in human-wildlife conflict. Contributing to local skill, I ran a training workshop in Nepal for local NGOs, national park staff, local researchers, wildlife trackers and guides so they could also learn how to use FIT and collect footprints of wildlife for conservation research.

My name’s Jody Tucker and I’m a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Forest Service. As programme lead for two long-term monitoring programmes, I’m responsible for work tracking the population status and trends of fishers and Pacific martens in the Sierra Nevada mountains, two species of conservation concern in the region. Large scale monitoring of such rare and elusive species across large and rugged landscapes is very difficult. Monitoring at this scale using capture based methods is cost prohibitive so we rely on a variety of non-invasive techniques to study these populations including camera traps, track plates, and hair snares. I’ve been working with WildTrack since 2019 using FIT to identify the sex of fishers and Pacific martens, and even individuals. This technology has the potential to greatly expand our analytical options for monitoring these species, which in turn will inform land management and species conservation. We have footprint track sheets for fishers and martens that have been collected for decades, so we also have the potential to use FIT technology to investigate the historical track collection too.

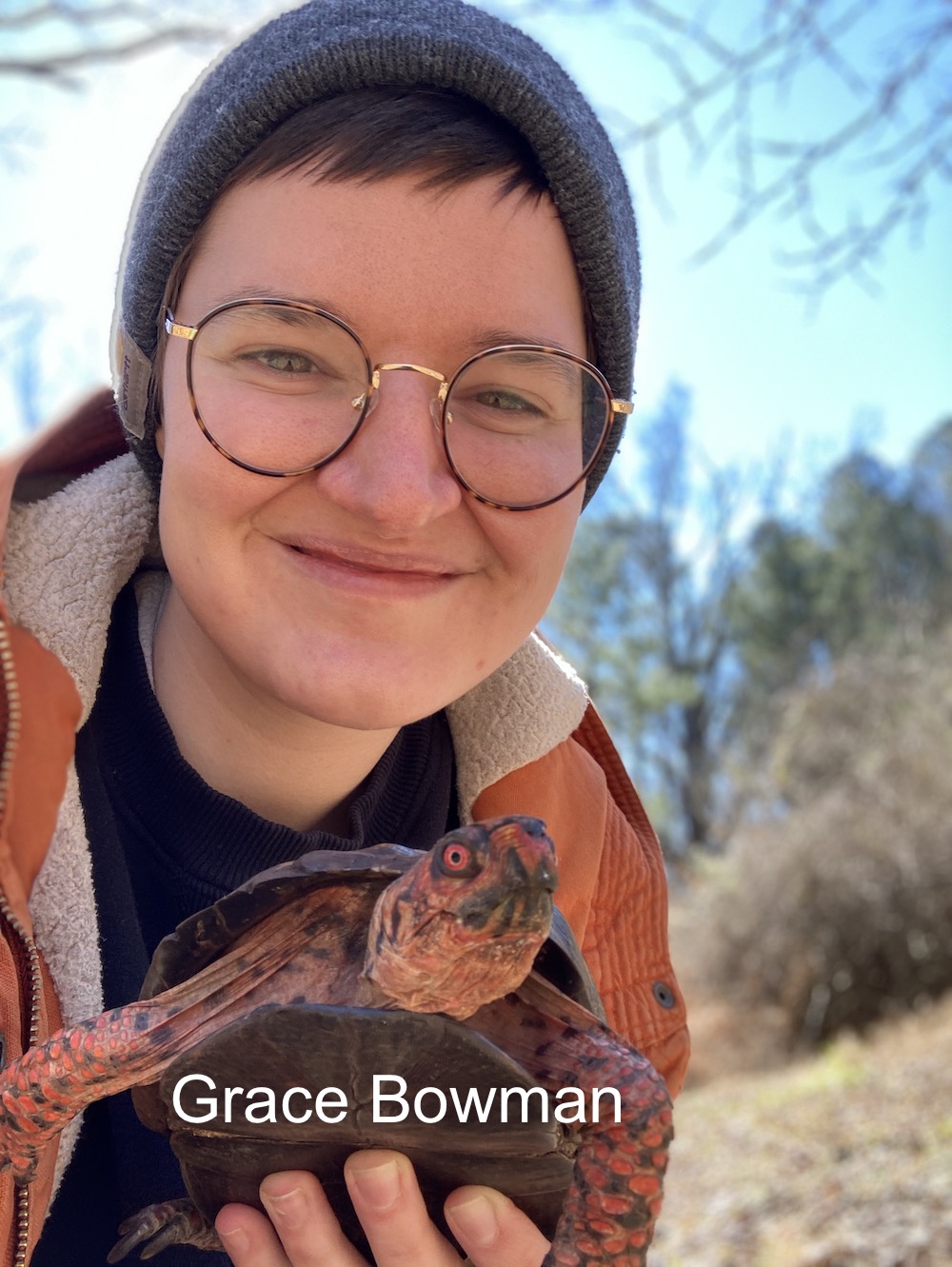

Hi, I’m Grace Bowman, and I’m the Conservation Assistant at Piedmont Wildlife Center in Durham, North Carolina. I study box turtles in the NC Triangle region in collaboration with WildTrack and a long-term project, Box Turtle Connection. I’m using FIT to analyse box turtle shells to test its efficacy in monitoring them in Leigh Farm Park, Durham, and hopefully beyond. We’re now planning a long-term project to develop an AI-powered turtle ID application for both citizen scientists and researchers.

As a strong advocate for animal rights and climate justice, I believe that ethical, non-invasive wildlife monitoring, as well as collaborating with the public in data collection, are key to successful conservation. I’m indebted to the many women that have mentored and trained me in my career, and I am honoured to work alongside them on these critical issues.

Hello! My name is Phoebe Griffith, and I’m a crocodilian scientist based at WildCRU, University of Oxford. I’m hoping to use evidence-based conservation to bring endangered species back from the brink of extinction. Crocs are really hard to study as they can be elusive and shy, spend a lot of time underwater, and are often active at night! At the moment I’m studying a really evolutionarily unique and pretty weird looking croc called a ‘gharial’ which is now only found in Nepal and India. Each gharial has a striped pattern on its back. Working with WildTrack, I’m hoping this unique pattern may enable us to identify individual gharials from photos, such as those taken from drones. This non-invasive monitoring method would allow much more accurate monitoring of population changes, which is so vital for a species which is critically endangered.

I’m Nida Alfulaij, and I steer the research programme at People’s Trust for Endangered Species (PTES), based in London, UK. We’re interested in endangered species around the world, and our native mammals here at home. I only recently joined WildTrack and am excited to be part of a global team which can share ideas, projects, and failures so we can all better plan conservation measures for threatened wildlife.

My particular interest is seeing whether we can use FIT to identify individual small mammals – not something we can do with other non-invasive technology yet. I work on hedgehogs and hazel dormice; both species are well-loved by the British public but both face many threats and have suffered serious declines. I’m especially concerned about their future in the face of our changing climate. As hibernators they may be particularly vulnerable and so the race to find measures to address their threats is really urgent.

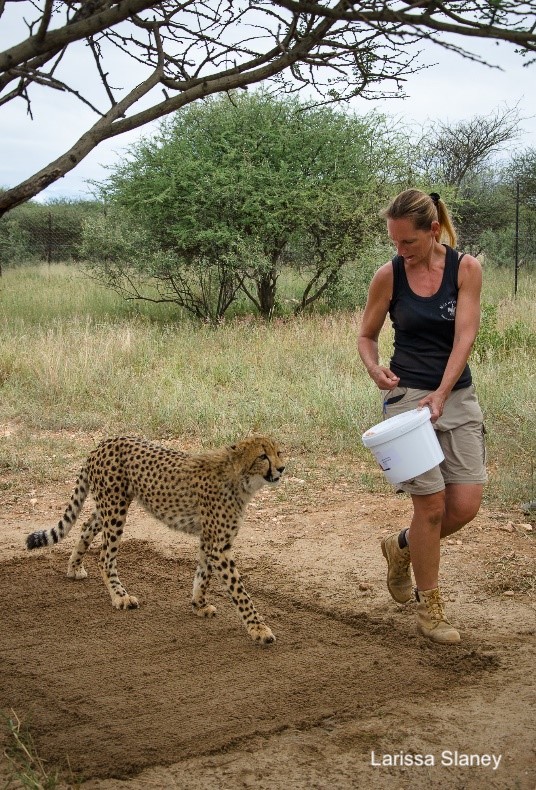

My name’s Larissa Slaney and I run the Fit Cheetahs research project at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, UK. Cheetahs are classed as vulnerable by the IUCN; two subspecies are so threatened that they’re listed as critically endangered. They face many threats across their range, all of which are exacerbated because as a species they have low genetic diversity. I’ve been working with WildTrack since 2017 and my research looks at how FIT can be used to monitor cheetabs more efficiently and cost-effectively in the field. We’re focussing on finding out if we can identify individuals, their sex, the subspecies and especially relatedness of individuals.

I’m working with the N/a’an ku sê Foundation in Namibia, Longleat Safari Park in the UK and Al Bustan Zoological Centre in the UAE. This means I’ve been able to collect footprints from almost 50 cheetahs of two subspecies, many of them are siblings or family units. Recently several US zoos have expressed an interest in supporting my research and I very much look forward to working with them. My hope is to include at least one more subspecies in my study. You can read more on my website or follow my research and cheetah conservation news on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.