I often like to describe the experience of working with green sea turtles (chelonia mydas) to that of working with modern day dinosaurs. A reptile – the green sea turtle’s ancestors evolved on land and returned to sea over 140 million year ago, having witnessed both the evolution and extinction of dinosaurs - yet today they are classified as Endangered by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Threats include habitat destruction and the loss of their nesting beaches, plastic pollution in the ocean (plastic bags can be mistaken for jelly fish by sea turtles and are responsible for a great number of deaths) and bycatch through commercial fishing practices.

I see a future where open source technologies and the sharing of knowledge will revolutionize the monitoring of species globally

As a Technical Specialist within the Zoological Society of London’s (ZSL) Conservation Technology Unit, it’s my job to research and understand how the latest technological advances can be utilised to better protect and conserve species and their habitats globally. I am a firm believer in the implementation of open source technologies and an advocate of knowledge sharing to drive forward open solutions to achieve this.

In the case of the green sea turtle, we recently embarked on a unique project to dramatically reduce the cost of tagging green sea turtles and acquire spatial and behavioural data using open source principles and technologies for the Principe Trust. The Trust’s goal is to promote the sustainable development of Principe island through research into nature conservation, tropical agriculture and education. Their turtle monitoring program actively patrols and protects the many beaches used by sea turtles across the island and they wanted to understand the movement of nesting turtles to better protect their important marine habitats.

Our plan was to deploy base stations on a selected nesting beach to collect spatial data from returning sea turtles as efficiently and as cost effectively as possible. (Image credit: Alasdair Davies)

It’s traditionally expensive to tag sea turtles and collect spatial data. You need a robust waterproof enclosure capable of protecting the electrical components inside at great depths, satellite connectivity and advances such as salt water switch triggers and fast GPS acquisitions to achieve a GPS lock within seconds when the sea turtles come up to the surface to take a breath. Commercial tags cost in excess of $2,000, and although well suited for the job and used extensively, we wanted to explore how new advances in open source manufacturing and technologies could achieve the same results, but at a dramatically reduced cost.

To do this, we worked with Luka Mustafa, a Shuttleworth Foundation Fellow and the founder of Inštitut IRNAS Rače. Luka’s team is pushing forward the boundaries of open source hardware development and design, having developed open tools such as the Troublemaker and the GoodEnoughCNC. They were tasked with the challenge of creating an enclosure to host a low cost Mataki tag and AX3 accelerometer. By utilising these open tools, we were able to design and 3D print a prototype enclosure at a fraction of the cost when compared to typical commercial prototyping.

The Process

1. An open Troublemaker 3D printer was utilised to print and evaluate our initial enclosure design. Physically printing our design ensured that we could load the tag with our payload of electronics to confirm that they could be positioned correctly and to evaluate the design.

2. A rubber base plate was cut and attached to assess the optimum drilling positions and base plate size. The tag was designed to be placed upon a base plate, that was then attached to the sea turtle using an epoxy solution - hence the tag’s code name “the pit stop tag”.

3. The completed 3D printed enclosure was taken to a sealant specialist to evaluate the use of polyurethane to form a seal between the acrylic lid and the tag’s base.

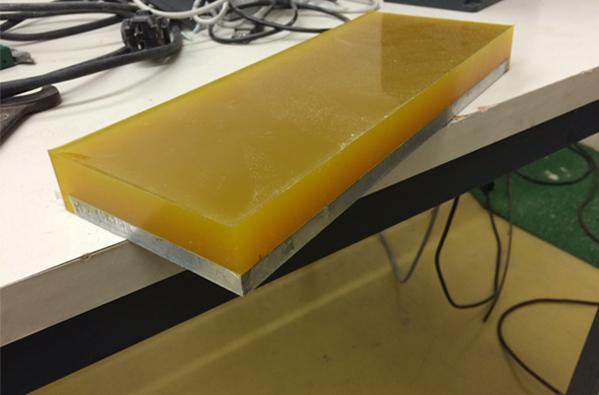

4. The polyurethane seal was devised by Tesnila Bogadi by pouring a liquid solution directly onto a thin aluminium plate and allowing it to cool before being cut to size and used to create each individual tag.

5. A completed tag with a connecting base plate can be seen in this CAD render. Later, we extended the footprint of the base plate so it was flush with the tag above to reduce the chance of potentially snagging on discarded fishing line when at sea.

The tags hold a Mataki, developed by Dr Robin Freeman of the Institute of Zoology at ZSL, which is capable of transmitting logged data wirelessly via radio to Mataki base stations within proximity. We wanted to place base stations on the known nesting beaches, tag the turtles with the new low cost tag and automagically acquire the logged data recorded by the Mataki when they returned to their nesting beaches. We nicknamed the tag the “Pit stop tag” as we designed it to be removable via a base plate, enabling researchers and beach guards to “swap” a tag out and replace it with a freshly charged tag without needing to apply fresh epoxy to attach and fix the tag in position.

Deploying the finished tag on a green sea turtle.

We trialled the tag in January (2016) together with researchers from the University of Exeter. Green sea turtles will lay clutches of eggs 4 – 5 times every 10 – 14 days, so we tagged a turtle on its third clutch (knowing that it was loyal to the beach) and waited patiently for it to return. When it did, we were delighted to successfully communicate with the tag and download its logged data. The tag’s enclosure costs ~$50 and the internal electronics $200, which is a dramatic cost reduction. Our next challenge is to explore and include an open source approach to rapid GPS acquisition and include a salt water switch to acquire reliable GPS locks when the turtles surface at sea.

Preparing the Mataki tags as payloads in the Pit Stop Tags.

We deployed 5 base stations to cover the entirety of the nesting beach. Each base station could pick up a returning sea turtle at up to 400 – 500m (LOS) once the turtle starts its haul from the water.

Caption: Each base station was powered by a 6 watt solar panel and is capable of communicating with a returning Pit Stop Tag at up to 400 – 500m away (868mhz)

Five base stations covered the entirety of the nesting beach.

I see a future where open source technologies and the sharing of knowledge will revolutionize the monitoring of species. Through the introduction of affordable and effective open solutions that are accessible to all, we can better collect, understand and analyse data, and importantly, act upon the knowledge acquired to make informed conservation decisions and ultimately protect and conserve endangered species such as the remarkable green sea turtle.

About the Author

Alasdair Davies is the Technical Specialist with Conservation Technology Unit, Zoological Society of London. He has over 10 years experience solving conservation challenges in the field through the implementation of viable technologies. His extensive knowledge in wireless & satellite connectivity helped to launch Instant Detect, a satellite connected alarm system for protected areas. As an advocate of open source hardware and software, Alasdair sees a future where open source technologies and the sharing of knowledge will revolutionize the monitoring of species globally.

Photo Credits

The header image is credited to Mike Davison and was used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0) License.

All images in the body article are credited to Alasdair Davies.

Add the first post in this thread.