Era of the Condor:

A Species' Future in Recovery

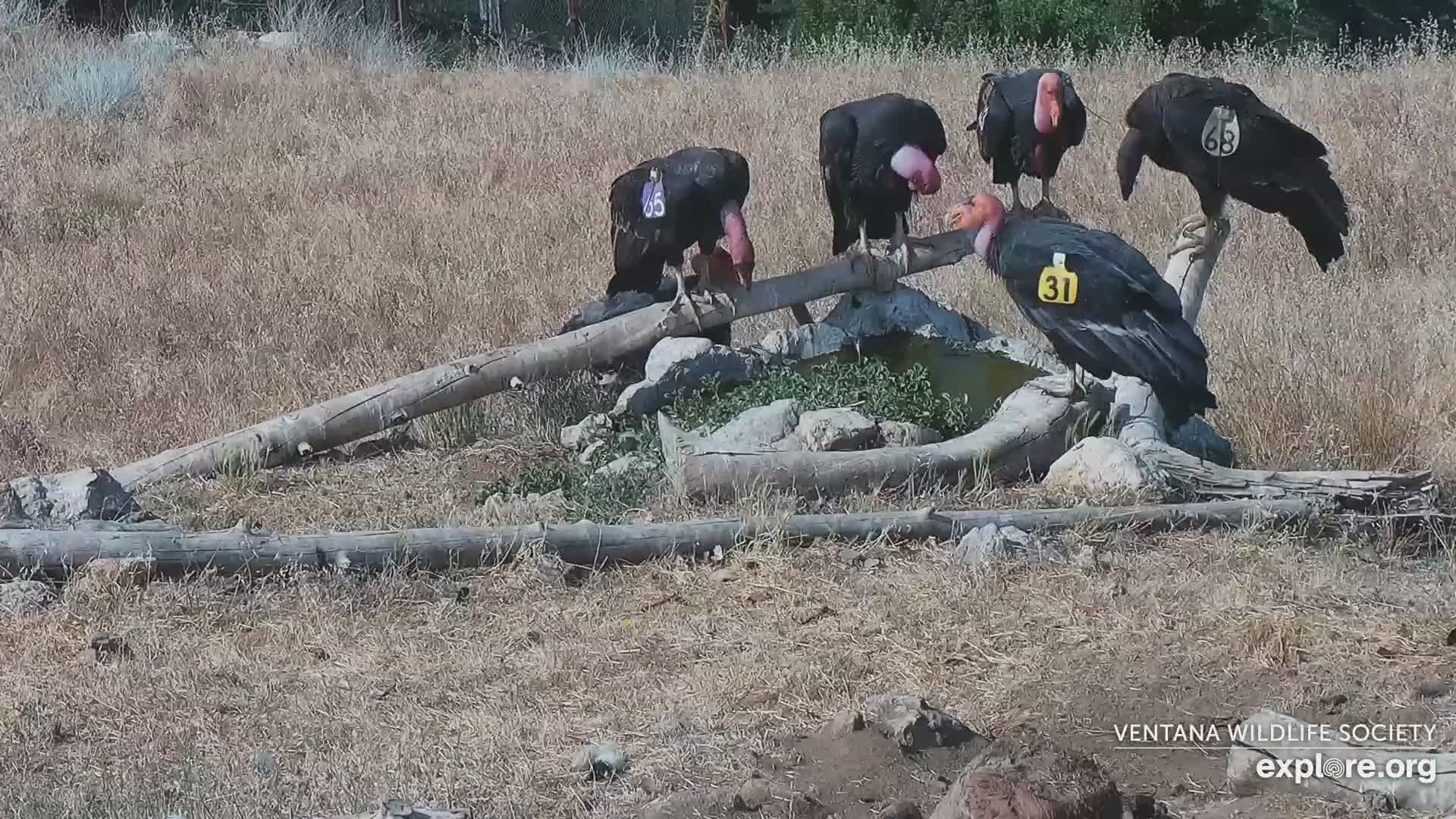

The story of the California Condor Recovery Program is one of conservation's greatest success stories, an unprecedented large-scale collaborative effort to save a species from the very brink of extinction. Using technology like GPS and VHF tracking, livestreaming cameras, digital databases, and unique captive breeding and rehabilitation tools, the conservationists devoted to saving the California Condor have seen populations grow from just 22 surviving birds to over 500 within three decades.

In part one of this series on the past and future of condor conservation, we looked at how the many teams involved in the California Condor Recovery Program use tracking technology and databases to great effect. And while tracking these birds is a crucial component to lowering the mortality rates caused by lead poisoning, the biggest threat against wild condor populations, a somewhat unexpected tool is addressing this issue from a vastly different angle. Where GPS and VHF tags meet this challenge with scientific data and well-honed strategies, live streaming cameras have risen to this challenge by creating a new, very personal way for people to study and connect with condors.

Photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

On the scientific side of things, live stream cameras in nests and at feeding sites provide condor scientists with an unprecedentedly rich understanding of condor behavior, breeding cycles, and social interactions. Rather than relying solely on brief field observations from naturalists sent across rugged terrain to bring back data on these famously elusive and hard-to-reach birds, scientists can now tune in unobtrusively to cams every day, observing the small behaviors and moments that may otherwise go forever unnoticed in the privacy of the condor's caves, or which may be disrupted by the presence of humans.

Photo courtesy of Molly Astell

Molly Astell from USFWS is one of the dedicated field biologists who deploys these cameras in nests, and she explains that they're vital management tools for intervening quickly when a condor is showing signs of lead poisoning or when a chick is injured or ill. As she describes it, the cameras are as much a support system for the condor chicks as they are for the condor conservationists themselves. Much like the recovery programs' tracking devices, live streaming cameras allow the team to respond far more rapidly in the field than they otherwise could. For a recovery program still focusing on individual-based strategies for a relatively small population, in which even a handful of mortalities can have long-lasting and far-reaching impacts, this ability is essential.

Photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

This system also frees up the recovery program teams to perform all the other tasks that are equally important to the condors' survival, like working with databases and volunteers, identifying regional lead poisoning threats, and deploying tracking devices. "We've had chicks with injuries, and because we had cameras on them, we could respond and monitor it, and leave it in the wild with us observing constantly through the cams," says Molly, "And then we go back in and intervene again only when it's necessary. So it's much less intrusive for the condors, with less human intervention and contact for them, and it's easier on us. it definitely relieves the stress of not knowing what's happening with that chick when you walk away."

Photo by Joseph Brandt, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

A traditional camera trap set-up may be effective for monitoring condor populations at popular feeding sites, but when it comes to capturing long-term behavior and development (like, for example, every milestone of a chick's life from hatching to taking flight for the first time), live streaming cameras blow other technologies out of the water. And as it turns out, the behaviors of condors and their round, fuzzy chicks are just as exciting to viewers around the world, who tune in to watch the continuing family adventures of condors who they've digitally known for years.

Video Credit: Cornell Lab Bird Cams on Youtube

By bringing the day-to-day lives of condor families directly into our homes, experts like Molly, Kelly Sorenson, Executive Director of VWS (the first organization to launch a condor cam), and Charles Eldermire, the Bird Cams Project Leader at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, believe that viewers will come to know and love these birds, and most importantly, love them enough to play their own role in minimizing threats to these growing but sensitive populations. Raw data helps scientists understand how best to protect condors, but live stream cameras help to bridge the mental gap between science and solving "a human problem," as Kelly called the challenges facing this species.

Photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Santa Barbara Zoo, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology

"The natural world always seemed to have an upper hand over the technology, in a big way."Charles Eldermire

Whether used for research or outreach, it's the steady advancement of technology which has made live streaming a viable part of the conservation playbook. The capabilities of these cameras mirrors the way the cameras in our phones have continually evolved since the early-to-mid 2000s. "Cameras have been used for as long as humans could get cameras to work," Charles tells me. "But at the same time, for studying wild things, they've been problematic because the natural world always seemed to have an upper hand over the technology, in a big way."

Considering the remoteness of condor territory (also a major factor in tracking device functionality, as discussed in Part One), miles from a solid WiFi signal, and the frequent threats of extreme wildfires, winds, and other unpredictable natural elements, the reliability of modern condor live streams is remarkable. "In, more or less, let's say the last twenty years or so, when there's been this explosion of weatherproof technology that can be deployed in places and survive the elements, they've become scientifically useful."

Video source: VWS on Youtube (VWS's current livestream cam is also placed inside of a redwood tree nest.)

And with that scientific benefit came the added plus of turning condor couples into beloved internet celebrities. Consider it conservation storytelling at its best, playing out in real-time, with the condors serving as the leads of their own communications team.

That, of course, extends to continuing to shift perspectives on using lead bullets in condor territory. "Helping people understand what is lost is what these cameras are best at illustrating. You watch and can't help but imagine what it feels like to be a huge condor with its wings out, basking in the light of the California sun. It's the opportunity to experience something authentic and light a spark. We let the birds reach people themselves. If legislation swings the other way, you don't need to just write a letter to convince someone that these birds are important; if they can watch, they'll know."

Photo courtesy of VWS and Explore.org. (Born in 2018 to condors Kingpin and Redwood Queen, Pasquale was the first chick livestreamed from the current redwood nest cam.)

Between the iconic color-coded indentification system used for condors, their long lifespans, and the live streaming boom, Kelly says it's easier than ever for people to keep up with their favorite condors. "We've got people who know these condors' entire family trees. They know their personalities. First the [color-coded] tags represented a temporary management system, and now they represent the importance of each individual bird being unique, and having a personality and family and story. It's why we don't just give them numbers, but names. Now the cams take that a step further."

"Consider it conservation storytelling at its best."

In a world heavily invested in reality tv shows, personal social media engagement, instant digital gratification, and relatability, live stream cameras offer a fresh and modern way to experience conservation. "It's engaging," Kelly continues. "They've seen these entire stories play out, and that creates a pretty special connection. You feel like you know them. And if you know them, hopefully you take the next step to wanting to protect them."

Similarly, Nadya Seal Faith of the Santa Barbara zoo has a favorite condor cam story about watching a bird she helped save from lead poisoning raise her new chick on a live stream cam; coincidentally, the chick shares Nadya's birthday, and the mother condor shares a birthday with Nadya's own mom! "It made me feel proud, and you do really feel like you're part of these condors' generations."

Video sources: VWS on Youtube

In fact, every condor expert who I speak to has their own collection of favorite stories about watching the live streams that they help to support. Molly, who hikes such great distances to deploy these cameras in the field, shared a memorable moment that serves as an example of how the littlest things can have enormous emotional impact. "This baby condor was simultaneously raising its toes for the first time. It was very methodical about it, really absorbed in this little action, and I thought, oh my god! I'm watching this little condor explore its world and discover something for the first time! You could just picture it thinking, 'Wow. I control these toes. These are mine.' It was just like watching a human baby discover that they control their own hands for the first time. And no one ever would've seen that moment without a cam."

Photo courtesy of VWS and Explore.org

The cost of cameras has gone down while quality has dramatically improved over the last decade (looking at archived videos from VWS's Youtube, you'll be able to see the difference between the current HD options and what field biologists previously worked with in the field). But as with any other conservation field work, technological and financial improvements don't make using and deploying this technology easy: they just make it a realistic option.

"Technological and financial improvements don't make using and deploying this technology easy: they just make it a realistic option."

So how do VWS and The Cornell Lab make sure that every cute, relatable, and scientifically significant moment can reach the internet from such remote sites? The technology used to broadcast these live streams across the world is not all that different from the system used to get tracking data back to base, requiring a network of tech elements interacting to ping each other across wide, rugged spaces.

Teams from USFWS, VWS, the Santa Barbara Zoo, and Cornell Labs have all worked together over the years to get these two main streaming systems up and running. Since 2011, these broadcasts have built steady followings by continually improving image quality, and cut costs as HD cams and broadcasting technology became readily available. Charles compares this shift to the cost of broadcasting a tv show on a major network versus a web series shot on a personal, high-quality camera. "At the rate they were being viewed, back then, it would’ve cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to maintain. But now we're able to work with more options to get these streams out to people, and with beautiful, immersive, HD imagery that we couldn't have imagined we'd have access to when we started."

Video Credit: Cornell Lab Bird Cams on Youtube

To get the signal from the cameras up and over the condors' mountainous terrain, The Cornell Lab and VWS rely on a complex, well-maintained network of solar-powered batteries, a series of progressive antennaes (a radio antennae might have to hit two or three repeater antennae setups to relay the message over ridges), fiber lines, and, of course, the cameras themselves. Eventually, the signal reaches a stable internet connection (out at Mt. Hopper, a high-powered antennae beams the signal to the Western Foundation for Vertebrate Zoololgy, another Recovery Program partner), and from there reaches another computer that connects to the streaming platform. It's a long way to travel in order to give viewers what feels like an instantaneous and effortless experience. According to Charles, the first cam network took a year to prep and achieve functionality.

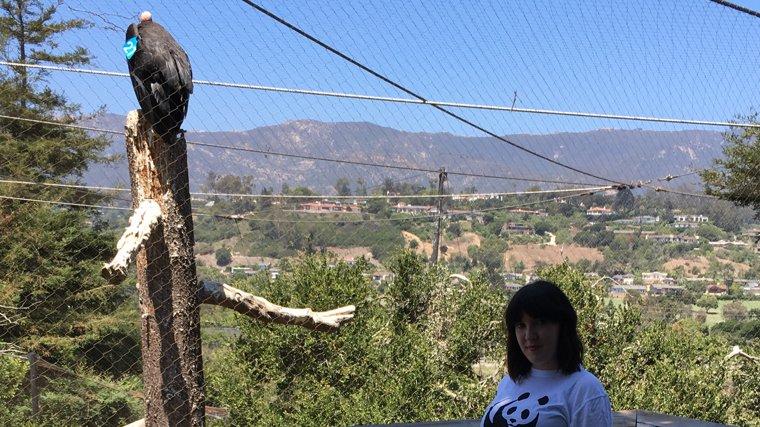

Photo courtesy of Molly Astell

Because of the scientific and public importance of these live streams, their maintenance is a major aspect of USFWS's fieldwork with the California Condor Recovery Program, and many big partners are willing to fund the necessary equipment; in fact, Nadya says organizations like the Disney Conservation Fund are working with them to expand the program and secure the right technology.

"It’s not really a money issue anymore as much as the landscape just being really challenging. The main difficulty is that locations are so remote and difficult to access,” says Molly as she describes the experience of deploying and troubleshooting on-site. “Maybe you know where link is down, maybe you don't. There are a lot of parts, not a lot of time, and if you don't bring the right gear and tools, that's a day lost," she says. "Ideally, you pack up one of everything, you've got this heavy, heavy pack. You take a long hike out there - at least a couple hours, sometimes three or four depending on the gear you're carrying - and some things you can test at the nest, some you can’t. If I head out there and I’m thinking maybe it’s the charge controller, that’s six hours of my day... and then it wasn’t even the charge controller! Sometimes it takes days to find out what’s wrong.”

Photo courtesy of Molly Astell

Like so many field conservationists who work with technology, those working on the condor teams have genuine and infectious enthusiasm for what they do, even on the longest days. "It's a lot of Type 2 Fun, you know what I mean?," says Molly. "During it, you’re like Argghh! You're stressed, you're tired, it's hot, the gear's heavy, you don't know what's wrong, you know you've got a long hike back. But then you get back from these cool places and think, well, that was actually a blast!"

"Sometimes you've just gotta McGyver out of a situation."Molly Astell

So what's Molly's biggest recommendation for anyone trying to troubleshoot tech gear out in the field, DIY-style? "Bike tube. I always carry it in my pack. Sometimes you've just gotta McGyver out of a situation, and it seems like I'm always fixing something with bike tube! You'd be surprised by what works, sometimes it's the weirdest thing. But if it does the job, great! Do it! So [bike tube]'s definitely ended up at some nest cam sites." (To learn more about Molly's work deploying and maintaining the condor cams, you can watch a Cornell Lab chat with Molly and other USFWS condor field biologists here.)

Photo courtesy of Molly Astell

The next ten years of streaming seem especially exciting for the Cornell Bird Lab and for Charles, who envisions even more rapid advancement and growth across the board. "I'd expect to see more and more easily executed solutions available every year to deliver this experience to viewers from more remote locations. Right now we're mostly broadcasting from places with main power access, and we don’t have resources for a fully off-the-grid camera system. But over time, the equipment lets us broadcast further and further."

Photo courtesy of VWS and Explore.org

Charles also expects to see another major leap in battery power efficiency as solar-powered options continue to evolve, and anticipates that future technologies will tap into data networks that don't exist yet. "Maybe we'll be dealing with super-fast satellite connections that we can't even picture yet. Instead of 4G or 5G, what could we do if we had 8G by then? A truly instantaneous connection?"

And as the streaming program improves alongside technology, Charles believes this program can find new and expanded uses for conservation efforts. "In those first six or seven years, we were just focused on growth. But now, we're shifting to understand what kind of further impact these cameras can make, and what service they can offer to the conservation world and researchers."

Photo courtesy of VWS

"It's the ability to stay connected, but let them be."Kelly Sorenson

As much as condor conservationists dream of a future in which their goals move away from the necessity for technologies like tracking devices as a means for survival, there are no objections to the condor cams continuing far, far into the future. Kelly tells me, "The goal is always to see them living independently, thriving, We'd be able to get rid of all the tracking technology and see them regain their original glory. But I do think we're always going to want to watch them. We'll always want to stay connected to them. That's what I'd dream for the future of the live streaming cams: it's the ability to stay connected, but let them be."

Photo courtesy of courtesy of VWS and Explore.org

Join us next week for the conclusion of the Era of the Condor series, focusing on captive breeding technology, how conservation technologists can get involved in the Recovery Program, and the future outlook for California Condors.

Interested in collaborating with the organizations involved in condor conservation or lending your tech expertise to them? Share your ideas and resources here on WILDLABS. This thread will be shared with our friends in the California Condor Recovery Program, and we hope it will serve as an ongoing place to connect the WILDLABS community with condor conservationists!

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A huge thank you to all the organizations and people involved in both of our condor articles:

Kelly Sorenson, Ventana Wildlife Society

Marti Jenkins, Oregon Zoo

Molly Astell, U.S Fish and Wildlife Service

Nadya Seal Faith, MSc, Santa Barbara Zoo

Charles Eldermire, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

We'd also like to thank all the press officers at these organizations who made our interviews possible, and thank those who have shared their photos and resources with us!

Header photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Santa Barbara Zoo, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

About the Author

WILDLABS writer Ellie Warren is a lifelong follower of the California Condor Recovery Program. Originally from Southern California, home of the condors, she first learned about the conservation efforts for this species in the 1990s at the San Diego Zoo, where she chose a plush condor chick as a souvenir and never looked back! You can find Ellie on Twitter, and email her at [email protected] with pitches for future feature articles, case studies, and other content ideas.

Add the first post in this thread.